I don’t know if it’s your cup of tea, but Neovide provides smooth scrolling at arbitrary refresh rates. (It’s a graphical frontend for Neovim, my IDE of choice.)

Programmer in NYC

I don’t know if it’s your cup of tea, but Neovide provides smooth scrolling at arbitrary refresh rates. (It’s a graphical frontend for Neovim, my IDE of choice.)

For some more detail see https://dev.to/martiliones/how-i-got-linus-torvalds-in-my-contributors-on-github-3k4g

It looks like there is at least one work-in-pprogress implementation. I found a Hacker News comment that points to github.com/n0-computer/iroh

Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. If the thinking is that AI learning from others’ works is analogous to humans learning from others’ works then the logical conclusion is that AI is an independent creative, non-human entity. And there is precedent that works created by non-humans cannot be copyrighted. (I’m guessing this is what you are thinking, I just wanted to think it out for myself.)

I’ve been thinking about this issue as two opposing viewpoints:

The logic-in-a-vacuum viewpoint says that AI learning from others’ works is analogous to humans learning from others works. If one is not restricted by copyright, neither should the other be.

The pragmatic viewpoint says that AI imperils human creators, and it’s beneficial to society to put restrictions on its use.

I think historically that kind of pragmatic viewpoint has been steamrolled by the utility of a new technology. But maybe if AI work is not copyrightable that could help somewhat to mitigate screwing people over.

That sounds like a good learning project to me. I think there are two approaches you might take: web scraping, or an API client.

My guess is that web scraping might be easier for getting started because scrapers are easy to set up, and you can find very good documentation. In that case I think Perl is a reasonable choice of language since you’re familiar with it, and I believe it has good scraping libraries. Personally I would go with Typescript since I’m familiar with it, it’s not hard (relatively speaking) to get started with, and I find static type checking helpful for guiding one to a correctly working program.

OTOH if you opt to make a Lemmy API client I think the best language choices are Typescript or Rust because that’s what Lemmy is written in. So you can import the existing API client code. Much as I love Rust, it has a steeper learning curve so I would suggest going with Typescript. The main difficulty with this option is that you might not find much documentation on how to write a custom Lemmy client.

Whatever you choose I find it very helpful to set up LSP integration in vim for whatever language you use, especially if you’re using a statically type-checked language. I’ll be a snob for just a second and say that now that programming support has generally moved to the portable LSP model the difference between vim+LSP and an IDE is that the IDE has a worse editor and a worse integrated terminal.

I pretty much always use list/iterator combinators (map, filter, flat_map, reduce), or recursion. I guess the choice is whether it is convenient to model the problem as an iterator. I think both options are safer than for loops because you avoid mutable variables.

In nearly every case the performance difference between the strategies doesn’t matter. If it does matter you can always change it once you’ve identified your bottlenecks through profiling. But if your language implements optimizations like tail call elimination to avoid stack build-up, or stream fusion / lazy iterators then you might not see performance benefits from a for loop anyway.

And there is also Nushell and similar projects. Nushell has a concept with the same purpose as jc where you can install Nushell frontend functions for familiar commands such that the frontends parse output into a structured format, and you also get Nushell auto-completions as part of the package. Some of those frontends are included by default.

As an example if you run ps you get output as a Nushell table where you can select columns, filter rows, etc. Or you can run ^ps to bypass the Nushell frontend and get the old output format.

Of course the trade-off is that Nushell wants to be your whole shell while jc drops into an existing shell.

I’m a fan! I don’t necessarily learn more than I would watching and reading at home. The main value for me is socializing and networking. Also I usually learn about some things I wouldn’t have sought out myself, but which are often interesting.

That’s a very nice one! I also enjoy programming ligatures.

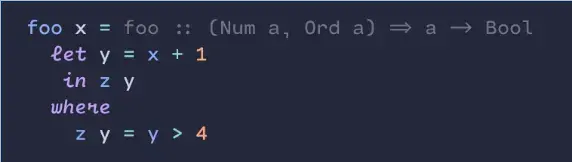

I use Cartograph CF. I like to use the handwriting style for built-in keywords. Those are common enough that I identify them by shape. The loopy handwriting helps me to skim over the keywords to focus on the words that are specific to each piece of code.

I wish more monospace fonts would use the “m” style from Ubuntu Mono. The middle leg is shortened which makes the glyph look less crowded.

Yes, I like your explanations and I agree that’s the way to think about it. But either way you have some special exceptions because main.rs maps to crate instead of to crate::main, and a/mod.rs maps to crate::a instead of to crate::a::mod. I know that’s the same thing you said, but I think it’s worth emphasizing that the very first file you work with is one of the exceptions which makes it harder to see the general rule. It works just the way it should; but I sympathize with anyone getting started who hasn’t internalized the special and general rules yet.

Yeah, it’s tricky that the file for a module is in a subfolder under the file that declared it, unless the file that declared it is named main.rs, lib.rs, or mod.rs in which cases the module file is in the same folder, not in a subfolder. There is logic to it, but you have to connect multiple rules to get there.

We see in the examples above that a module named whatever can be in whatever.rs or in whatever/mod.rs and you get the same result. mod.rs is a special name with a special lookup rule.

whatever/mod.rs whatever/submodule_of_whatever.rs works exactly the same as whatever.rs whatever/submodule_of_whatever.rs. We use mod.rs so we don’t have to have both a folder and an .rs file with the same name. But that leads to the special exception where submodules declared in mod.rs are defined by files in the same folder as mod.rs.

main.rs is like the mod.rs of the entire crate. main.rs has a special rule where it’s in the same folder as its submodules, instead of the normal rule where submodules are in a subfolder.

lib.rs fellows the same special rule as main.rs. (You use main.rs to define an executable, lib.rs to define a library.)

git rebase --onto is great for stacked branches when you are merging each branch using squash & merge or rebase & merge.

By “stacked branches” I mean creating a branch off of another branch, as opposed to starting all branches from main.

For example imagine you create branch A with multiple commits, and submit a pull request for it. While you are waiting for reviews and CI checks you get onto the next piece of work - but the next task builds on changes from branch A so you create branch B off of A. Eventually branch A is merged to main via squash and merge. Now main has the changes from A, but from git’s perspective main has diverged from B. The squash & merge created a new commit so git doesn’t see it as the same history as the original commits from A that you still have in B’s branch history. You want to bring B up to date with main so you can open a PR for B.

The simplest option is to git merge main into B. But you might end up resolving merge conflicts that you don’t have to. (Edit: This happens if B changes some of the same lines that were previously changed in A.)

Since the files in main are now in the same as state as they were at the start of B’s history you can replay only the commits from B onto main, and get a conflict-free rebase (assuming there are no conflicting changes in main from some other merge). Like this:

$ git rebase --onto main A B

The range A B specifies which commits to replay: not everything after the common ancestor between B and main, only the commits in B that come after A.

It’s because new phones are too big! I’m planning to take my reasonably-sized phone to the grave!

Huh, I hadn’t heard about any of this. I guess that’s because I use Google Voice, and none of the features going into the Messages app have made it over to the Voice app.

My main game continues to be Overwatch.

I’ve also been playing some Diablo IV. I’ve been taking my time - there is a lot to enjoy in that game. I just teamed up with my brother to finish the last act of the main story.

You’re welcome!

Have you tried using the #[debug_handler] macro on get_all_armies? Without that macro handler errors don’t tell you much more than “something isn’t right”.

Generally this kind of error indicates some type in the handler signature doesn’t implement a necessary trait. Maybe you accidentally lost an automatically-derived trait like Send + Sync? The macro is the easiest way to check.

rust-script looks like a neat way to use Rust for scripting. But I was coincidentally reflecting on how helpful Nix is for handling the same problem, where I want to write scripts in a compiled language, but managing builds is a lot to deal with in an ad-hoc setting. I can pair my script with a Nix expression that gets checked into either my project repo, or my Home Manager dot files, and then I don’t have to think about rebuilding on changes or on new machines.

I’ve had ls aliased to exa for a while. So it looks like eza is a fork of exa? The git feature looks interesting.

It scrolls smoothly, it doesn’t snap line by line. Although once the scroll animation is complete the final positions of lines and columns do end up aligned to a grid.

Neovim (as opposed to Vim) is not limited to terminal rendering. It’s designed to be a UI-agnostic backend. It happens that the default frontend runs in a terminal.